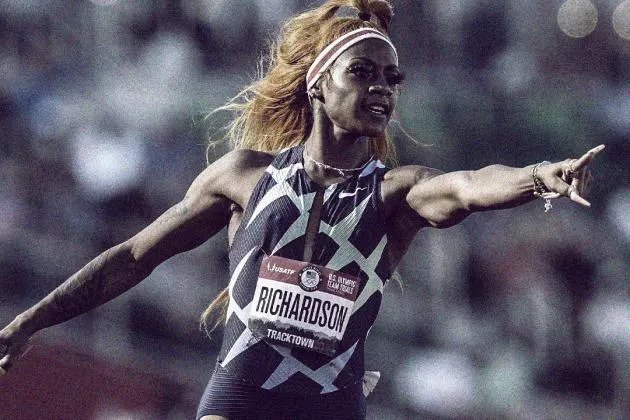

The reason Sha’Carri Richardson won’t run the 100 meters in Tokyo is only partially about marijuana.

Richardson’s 30-day suspension, which she accepted after failing a drug test at U.S. Team Trials, doesn’t actually prevent her from participating in the Olympics. Instead, it disqualified her Trials performance, and Team USA’s selection standards say its three 100m slots go to the three fastest runners at that one meet.

It’s an important distinction, given that Richardson’s suspension ends a few days before the track portion of the Olympics is set to begin. If the U.S. chose its Olympians like they do in Canada or Kenya or Great Britain, for example, the country’s fastest woman would likely be on the starting line in Tokyo. But unlike those countries, which have some discretion in their selection process, the USA Track & Field bylaws leave no wiggle room—a bad performance at Trials means you don’t qualify for the Olympics in that event.

In some cases, however, it also works the other way. Not only was Richardson the fastest American woman this year, she’s also the country’s most recognizable young track star. Not having her compete in Tokyo is a loss for almost every U.S. Olympics stakeholder, including team sponsor Nike and U.S. broadcaster NBC.

“There is some irony to it,” said Mark Nagel, a sports management professor at the University of South Carolina. “You’d think that in most cases a country and governing body would try to manipulate things so they’d have the best chances to win a medal at the Olympics. The U.S., in a lot of ways, is being somewhat noble by following the letter of the rules, even if it hurts the ultimate medal goal.”

Representatives for USATF didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment. The group said in a statement after it announced its 4×100-meter relay team (Richardson’s last hope at running in Tokyo) that it would be “detrimental to the integrity of the U.S. Olympic Team Trials” if the rules were changed in the run-up to the Tokyo Games.

USATF claimed about $105.6 million in revenue in the four years from 2013-2016, a large majority of which comes from marketing partners like Nike, Toyota and Hershey. And like most national governing bodies, the Olympics year is the critical one. It includes the Summer Games themselves, of course, but also the Trials, where ticket sales and sponsorship pull in critical revenue. (The Trials, which are hosted by TrackTown USA, show as a roughly $5 million revenue line item on USATF’s tax returns).

Trials are extra important because of the sport’s status in the U.S. Unlike in parts of Europe, where annual meets draw fans and TV eyeballs, casual American sports fans only really follow track for a few months every four years.

“We have not seen any sponsorship drop as it relates to the execution of our Trials,” which were postponed from last year, USATF CEO Max Siegel said at an interview last month. The event, held at the University of Oregon’s new $270 million Hayward Field, allowed about 8,700 fans at a time.

Many experts say the USATF bylaws, which are agreed upon by the USOPC, show proper governance. For one, it helps the sport avoid selection drama common in sports like gymnastics, where teams are assembled more subjectively. It also establishes a clear, fair and consistent guideline for all athletes that can’t be altered due to any outside influence or bias.

“If you go the route of establishing a ‘free card’ for Olympics participation, bribes and all the things we don’t want in sports become a big concern,” said Lisa Delpy Neirotti, an Olympics scholar and director of the Sport Management Program at the George Washington University School of Business. “Do we want that? I think you’re opening Pandora’s Box if you’re suggesting that USA Track & Field create a forgiveness policy or a one-off policy.”

That’s helpful on the business side too, according to Delpy Neirotti. “I think sponsors prefer to work with a professional governing body that follows due process,” she said.

The USATF rules, however, aren’t without high-profile moments. In the run-up to the 1992 Summer Games in Barcelona, a lot of attention was directed at American decathletes Dan O’Brien and Dave Johnson—known simply as “Dan & Dave” due to a Reebok marketing campaign. Despite the hype and the obvious talent, O’Brien missed the pole vault during Trials and failed to qualify for the Olympics.

There’s also some absurdity. Consider American jumper Christian Taylor, who has won the last three World Championship titles in the men’s triple jump. By virtue of being defending champion, he is given an automatic wild-card entry into the following Worlds, but he still needs to show up at nationals that same year. So in his first “jump” he’ll simply walk down the runway, take a foul, then pass the rest of his jumps.

Richardson’s situation is further complicated by the fact that she was also eligible to be chosen for the 4×100-meter relay in Tokyo (while individual events are determined at Trials, the final two relay participants are chosen by a small panel). Richardson was not chosen for the relay—the other runners had been informed of their selection before her test results were known, and the bylaws don’t mention substitutions.

“Sha’Carri Richardson is a good person, and good for the sport. It hurts her and it hurts USATF to keep her off the relay and out of the Olympics,” said Victoria Jackson, a former professional runner who teaches sports history at Arizona State University. “I hope this serves as the motivation to modify the rules so that an athlete in a situation like hers, or a future sprinter who false starts and is disqualified, can still be an Olympian by being included in the relay.”

Source: yahoo.com